Standing in front of the South Gate, you raise your eyes to see the exquisitely elegant roof of the main hall from the Tenpyō era. However, it may surprise you to learn that Ganjin (Jianzhen) never actually saw this hall. This is not because he had lost his eyesight, but because the main hall did not exist during his lifetime. It is not uncommon for ancient temples and shrines to look completely different from how they did when they were first built. In fact, this is often the case. It was a refreshing surprise to discover that the connection between Ganjin and the main hall of Tōshōdai-ji, something we had firmly associated in our minds since history class, was contradicted by the facts. It reignited a sense of excitement, reminding me just how fascinating history can be!

This time, I was invited by an acquaintance to participate for the first time in the September gathering of Nara’s “Tenpyō-kai,” which has been ongoing for 80 years. I was fortunate to have a valuable experience visiting Saihōin and Tōshōdai-ji, led by a talk from Professor Takahide Sugisaki of Tezukayama University.

In ancient history, there is more that remains unknown than known, and there are few things that can be stated with 100% certainty. Perhaps that’s exactly why ancient history sparks our imagination and is so fascinating. While it’s important to have knowledge that aligns as closely as possible with what we believe to be facts, it’s the stories behind those facts that make history truly interesting.

Today at Tōshōdai-ji, I saw a teacher leading a group of students on a school trip, explaining, “This is an Important Cultural Property, and this is a National Treasure.” That’s such a dull explanation. It may be factual, but without any story, the students probably just let it go in one ear and out the other. Listening nearby, I couldn’t help but feel a bit disappointed, thinking that history can be so much more enjoyable.

History

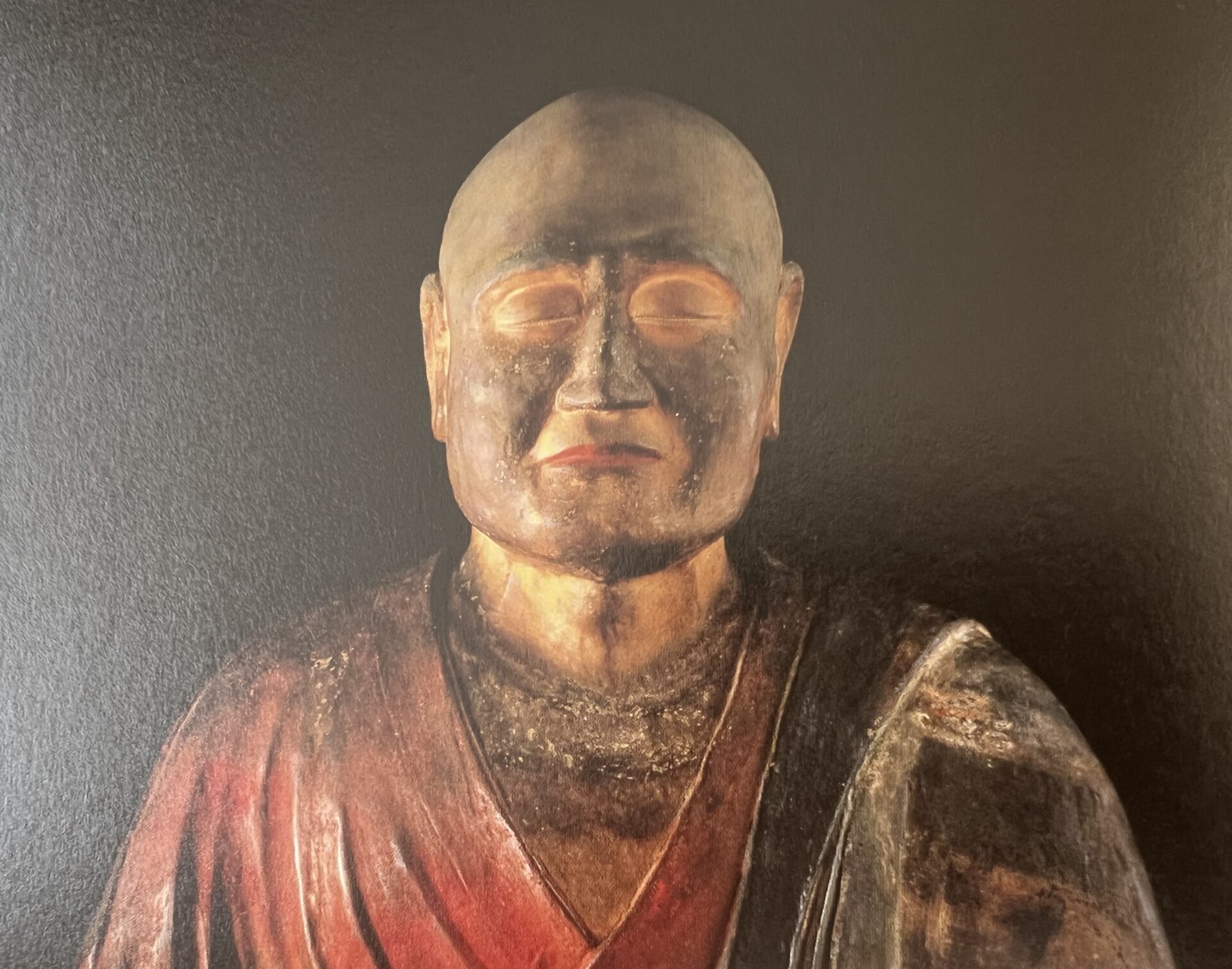

Tōshōdai-ji was founded in 759 (the 3rd year of the Tenpyō Hōji era) as Ganjin’s private temple on the former residence of Prince Nitanabe. After his son, Prince Funado, was implicated in the rebellion of Tachibana Naramaro against Empress Kōken and died in prison, the estate became the site of Tōshōdai-ji. The sutra repository from Prince Nitanabe’s residence still remains within the temple grounds, and it is the oldest structure at Tōshōdai-ji. There’s also a somewhat eerie story that the imperial inscription at Tōshōdai-ji was handwritten by Empress Kōken herself.

With the founding of Tōshōdai-ji, the Higashi Chōshūden (a building where government officials worked) from Heijō Palace was relocated to the temple grounds. Since Tōshōdai-ji was a private temple, it is believed that it was not financially well-off in its early days, which may be why the temple was granted the building. Ganjin passed away in 763 (the 7th year of the Tenpyō Hōji era), and over the next 50 years, his disciples, such as Hōsai and Nyohō, continued his work, gradually completing the temple complex.

The period during which Tōshōdai-ji was founded and gradually took shape coincides with the end of Empress Shōtoku’s (Kōken’s) reign, daughter of Emperor Shōmu, and the era when Emperor Kanmu moved the capital from Heijō-kyō to Nagaoka-kyō and later to Heian-kyō. This overlap between the transition from Nara to Heian is particularly fascinating.

Main Hall

The main hall, cherished by many scholars and artists, is a masterpiece of Tenpyō-style architecture, featuring eight entasis columns. Recent scientific investigations have revealed that some of the timbers used for the hall’s rafters were cut in 781, indicating that the main hall was not completed before that time. In other words, the hall did not exist during Ganjin’s lifetime. The Tōshōdai-ji temple complex was completed in 810, the first year of the Kōnin era, with the construction of the main hall corridors and the east pagoda under Emperor Heijō’s reign.

I was thrilled to learn that there is a theory suggesting the current principal image, the seated statue of Rushana Buddha, may have been made for Empress Kōmyō. When I asked Professor Sugisaki about this, he mentioned that a paper on the topic was published in the 2023 edition of “仏教芸術 Buddhist Art,” and I am determined to read it.

Lecture Hall

The lecture hall is the oldest building relocated from Heijō Palace, yet it is known from inscriptions that the principal image of Maitreya Buddha seated inside was created much later in 1287 (the 10th year of the Kōan era), meaning the statue is actually newer than the building itself—a fascinating reversal.

It is believed that the current principal image of the main hall, the Rushana Buddha, was originally enshrined in the lecture hall during Ganjin’s time and was moved to the main hall when it was completed. This kind of shifting of Buddha statues between halls over time, as seen at places like Tōdai-ji, seems to have been quite common.

Shin-Hozo (Treasure Hall)

Tucked away deep within the temple grounds, the Shin-Hōzō (New Treasure House) is a must-see, displaying many temple treasures. These include six newly designated National Treasures (despite being damaged) as well as the famous original shibi (ornamental roof finials) from the temple’s founding and Empress Kōken’s imperial plaque. There’s no air conditioning, so it can get quite warm in the summer, but it’s definitely worth a visit.

This time, a rare and elegant standing statue of Prince Shōtoku was on display. Even if it’s not mentioned in history books, considering the close relationship between three generations of women—Tachibana no Michiyo, Empress Kōmyō, and Emperor Kōken (Shōtoku)—it’s not surprising that the faith in Prince Shōtoku, which began with Tachibana no Michiyo, was passed down to her granddaughter, Emperor Kōken (Shōtoku). Lost in this imagination, I found myself captivated by the beautiful childhood statue of Prince Shōtoku.

Treasures

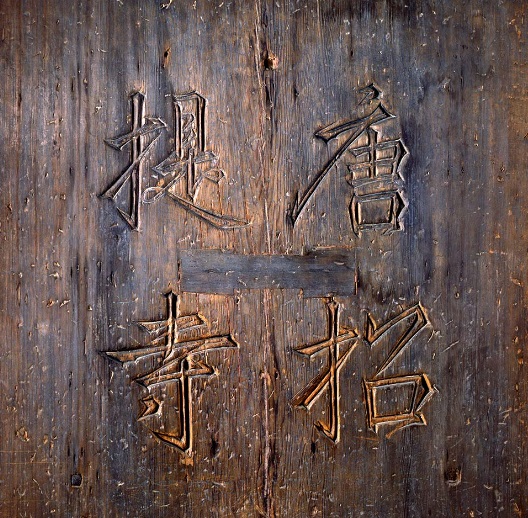

Tōshōdai-ji has nearly 30 National Treasures, and as it’s not possible to cover them all, I will mention only a few.

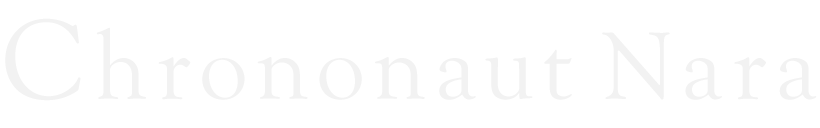

–National Treasure: Seated Statue of Ganjin Wajō (Miei-dō) – Dry lacquer technique

Upon closely examining the statue of Ganjin Wajō, it was discovered that several white objects are embedded within it. There is a theory that these may be part of Ganjin’s remains (a bit eerie!).

–National Treasure: Seated Statue of Rushana Buddha (Main Hall) – Dry lacquer technique

–National Treasure: Standing Statue of Thousand-Armed Kannon (Main Hall) – Wood-core dry lacquer technique

–National Treasure: Standing Statue of Yakushi Nyorai (Main Hall) – Wood-core dry lacquer technique

–National Treasure: Standing Statue of Bodhisattva Shūhō-ō (Shin-Hōzō) – Wood

–Important Cultural Property: Standing Statue of Buddha (Shin-Hōzō) – Wood

It was explained that the statues at Tōshōdai-ji are highly valuable as they represent the transitional period from dry lacquer to wooden sculpture techniques.

Flowers

The temple grounds offer an abundance of flowers, green leaves, and autumn colors to enjoy throughout the year.

When I visited in September, it was the season for bush clover (hagi).

In spring (April to May), keika, a flower native to Ganjin Wajō’s homeland, blooms. In summer, irises and lotus flowers are beautiful, and in autumn, the grounds are adorned with vibrant autumn leaves. Additionally, the moss around Ganjin Wajō’s gravesite is a highlight.

Access

Get off at Nishinokyo Station on the Kintetsu Kashihara Line. It’s a 10-minute enjoyable walk from there.

If you’re coming from Kintetsu Nara Station, transfer at Saidaiji Station, and it’s just two stops, so you’ll arrive in about 20 minutes. From Nishinokyo Station, turn right to go to Yakushiji, or left to go to Tōshōdai-ji.